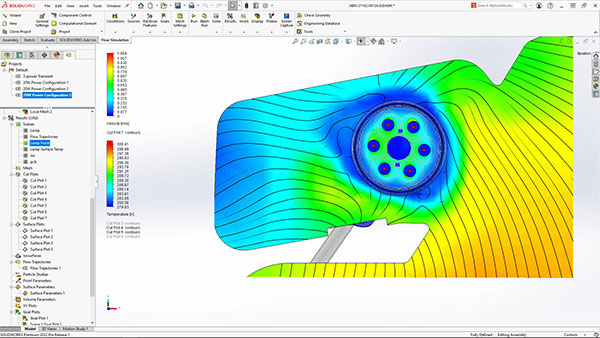

CFD simulation is integrated into the SOLIDWORKS CAD program. Image courtesy of SolidWorks.

Latest News

May 12, 2023

Simulation-driven design became the engineering community’s mantra in the last decade. This was driven in part by the software vendors’ proposition that virtual tests are much easier and cheaper than destructive physical tests.

In aerospace and automotive, the economics clearly favor virtual tests. According to Boeing’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, a typical wind tunnel session takes about 45 hours, at a price tag of $40K.

On top of that, add another $1 million to build a physical aircraft model (“Symbiosis: Why CFD and wind tunnels need each other,” Joe Stumpe, June 2018, Aerospace America, published by AIAA).

Though the financial argument is solid, several forces must converge to make the mantra a reality. For this article, Digital Engineering decided to single out three enabling factors: (1) ease of use of simulation applications; (2) user adoption; and (3) access to computing power: Are these pillars of simulation-driven design as solid as the financial argument?

We asked Joe Walsh, founder of IntrinSIM and director of Analysis, Simulation & Systems Engineering Software Strategies (ASSESS), to assign grades to each enabler.

Software Ease of Use: Vendors Get A-, B+

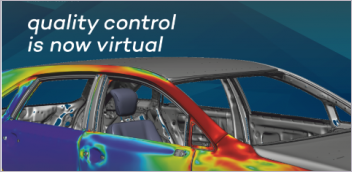

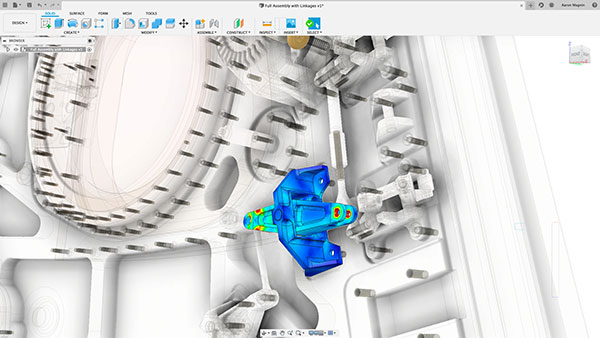

For designers to use simulation tools in the conceptual design phase, tools need to be easily accessible. The user interface must be reengineered to suit the target audience. It involves integrating simulation features in CAD design packages and simplifying input fields to set up simulation runs.

“For simulation-driven design, this is a necessary step to make simulation tools part of the design process,” says Walsh. “If simulation remains a separate validation tool, it’s a struggle to connect it to the design process to drive design decisions.”

Autodesk, Dassault Systèmes, PTC and Siemens have all made concerted efforts to integrate simulation tools into their mainstream design programs, such as Autodesk Fusion 360, SOLIDWORKS, PTC Creo and Siemens NX. Simulation software maker Ansys now offers Ansys Discovery, an easy-to-use, cloud-based simulation program with near-real-time responsiveness. Also emerging are browser-based pay-per-use simulation vendors such as SimulationHub.

“On the vendors’ efforts on that front, I’d give them something between an A- and a B+,” says Walsh. “They’ve done significant work, so simulation is now approaching real time. They’ve made the solvers faster, easier to set up. But someone [a simulation expert] still has to set up the problem to solve.”

To clarify, Walsh is not advocating removing the human expert from the simulation process. “I don’t think they’ve made much effort to capture the people’s expertise to go to the next step,” he says.

In 2014, COMSOL added Application Builder to COMSOL Multiphysics software, its flagship offering. It allows expert simulation users to publish templates and workflows so novices and designers can use them as a guided setup for complex simulations.

User Adoption: Users Get B, C

Simulation-driven design is a new approach, a new way of working, so it runs up against the human tendency to resist change and stick to the comfortable status quo, but Walsh doesn’t think it’s fair to criticize the users.

“For them to move from standard design processes to simulation-driven design, they must fundamentally change their design processes. They must have a justification and compelling reason to do that, because with a new process, you’re introducing a lot more risk,” he says.

If taking full advantage of the simulation tools at their disposal is viewed as the ultimate success (A), and taking no advantage of the tools is seen as a failure (F), where might Walsh put the user community as a whole?

“Since they have access to it, but they’re only taking advantage of some of it, I’d give them a B or C. Like I said, there are some legitimate issues preventing them from using it. But those who are not even entertaining the idea of using it, I’d give them a D or F,” he says.

Computing Power Access: Hardware Suppliers Get A-

At its core, finite element analysis (FEA) programs are a set of partial differential equations. From model meshing to stress calculation, computing power determines how much or how little time it takes to execute the tasks.

Previously, parallel processing on multicore CPUs sped up simulation, but later, when graphics processing unit (GPU) maker NVIDIA decided to pivot its hardware to general purpose computing, simulation speed began to accelerate. New opportunities arose with affordable on-demand computing, catapulting simulation to new heights and scale. In the past, workstations and servers were the standard requirements for simulation. Today, engineers can run large-scale simulations with a standard laptop, connected to on-demand servers via a broadband connection.

For their work to facilitate simulation-led design, “hardware vendors get [an] A-,” Walsh says. The hardware—on-demand or on-premises—is robust enough for simulations involving moderate to complex physics, he says. “But as soon as we get to really complex physics, like electromagnetics and crash simulations, even with a powerful high-performance computing [HPC] system it still takes weeks in my experience.”

As generative design and systems design become more common, Walsh anticipates the need might outpace the available hardware power.

Accuracy Guided by Purpose

Walsh thinks the industry needs a guide—a cheat sheet, if you will—to help them decide the level of accuracy required to make various engineering decisions. A one-size-fits-all approach is not recommended.

“For example, in the early concept stages, I’m just looking for general trends, so if I have a system that’s plus or minus 20%, and the errors are consistently in the same direction, that’s good enough. But if I’m getting close to the final release, if I’m in the detailed design stage to figure out certain strategies for stress relief, that’s not good enough,” Walsh says. “The desired quality of the simulation increases as the design progresses.”

As part of ASSESS’ advocacy work, the Engineering Simulation Credibility Working Group recently published a paper titled “Understanding an Engineering Simulation Risk Model.” The paper describes the risk model as “a predictive capability assessment that includes a set of recommended best practices and associated metrics to understand and manage the appropriateness and risk associated with engineering simulation influenced decisions.”

Drawing on NASA’s requirements and criteria, the paper maps out the recommended modeling and simulation quality in relation to the consequences of the engineering decision. It also proposes assigning a level to the Predictive Capability Maturity Model, from 1 (little or no assessment of the accuracy and completeness) to 5 (formal assessment of the accuracy and completeness).

For assessing modeling and simulation, the following criteria are recommended by the ASSESS Engineering Simulation Risk Model to determine an “Appropriateness Index:”

- Usage

- Pedigree

- Verification

- Fidelity

- Validation

- Uncertainty

- Robustness

More ASSESS Initiative Coverage

More Autodesk Coverage

More Dassault Systemes Coverage

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at kennethwong@digitaleng.news or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE